Algernon Blackwood's Cosmic Estrangement

“There’s places in there nobody won’t never see into.” — The Wendigo1

In his youth, Algernon Blackwood, son of a wealthy English family, was shipped off to Canada from London for some practical life experience. Blackwood’s first venture was a dairy farm in Islington that was doomed to fail. Regardless of his efforts, the milk always soured. The cause, he later remarked with superstition, would “always remain a mystery.” Those familiar with agrarian folklore might easily infer why.

From a young age, Blackwood was attuned to what one might call the supernatural. His evangelical parents had sent him to a Moravian Brotherhood in Germany to study, where he developed a lasting reverence for nature as an expression of some greater cosmic mystery.

“Those leagues of Black Forest rolling over distant mountains, velvet-coloured, leaping to the sky in grey cliffs, or passing quietly like the sea in immense waves, always singing in the winds, haunted by elves and dwarfs and peopled by charming legends… It all left upon me an impression of grandeur, of loftiness, and of real religion, and of a Deity not specially active on Sundays only.”2

At seventeen, he discovered a book of Hindu aphorisms left in his father’s study which he read secretly by candlelight. The words felt strangely familiar, “as if I had known these truths before”, he reflected, “it marked the opening of my mind”. His “singular conviction of the unity of life everywhere and in everything” had taken root. The material world was only a symbolic veil obscuring “some intensely beautiful reality.”2

Disillusioned by life’s hardships after yet another failed enterprise reviving a seedy hotel in downtown Toronto, Blackwood admitted defeat. He had “no appetite for business”. At the invitation of a friend he escaped the city and headed north, with only a few books of Eastern philosophy and a Steiner fiddle under his arm, into the backwoods of Ontario…

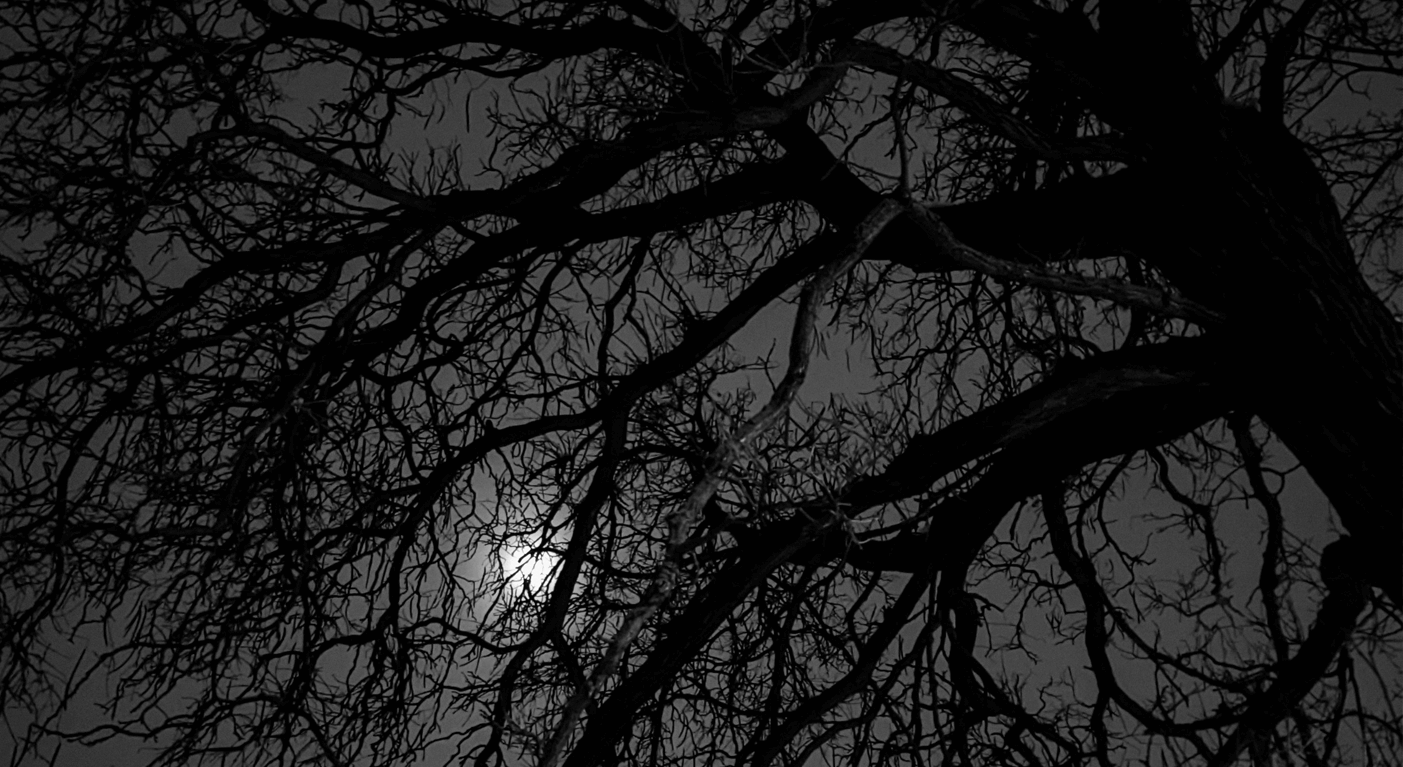

In 1892, Blackwood made camp on what is now North Bohemia Island in Lake Rosseau. Here he began to collect the observations that would come to shape his masterfully moody nature writing. He described the time as a “fairyland existence” that countered the “furious turmoil of the noisy city” He found solace in “lonely campfires, the moonrise and stars over the water, and the quiet of pine forests.”2 With no mention of the nefarious blackfly, it seems he was thoroughly enchanted.

“Nature introduced a vaster scale of perspective against which a truer proportion appeared. There lay in the experience some cosmic touch of glory that, by contrast, left all else commonplace and unimportant. The great gods of wind and fire and earth and water swept by on flaming stars, and the ordinary life of the little planet seemed very small, man with his tiny passions and few years of struggle and vain longings, almost futile. One’s own troubles, seen in this new perspective, disappeared.”2

In that sublime touch of cosmic glory, Blackwood discovered a “valuable expansion of conscious- ness”, a dethroning of the human as the center of meaning. In his tales, characters often question whether events occur in the external world or within the mind. They fear dwelling too long on strange thoughts, lest those thoughts materialize. Well-versed in the immaterialism of George Berkeley and radical empiricism of William James, Blackwood presents a reality in which thought and perception do not just mediate experience, but constitute it. When the familiar coordinates of mind and matter come adrift, the wild may manifest as a sentient presence.

“The early feeling that everything was alive, a dim sense that some kind of consciousness struggled through every form, even that a sort of inarticulate communication with this other life was possible, could I but discover the way.”2

Blackwood’s fiction is animated by the eerie intuition of nature as alien agency, an otherness that disturbs the mind yet ultimately belongs to the outside, beyond articulation. The weird always exceeds what reason attempts to explain away.

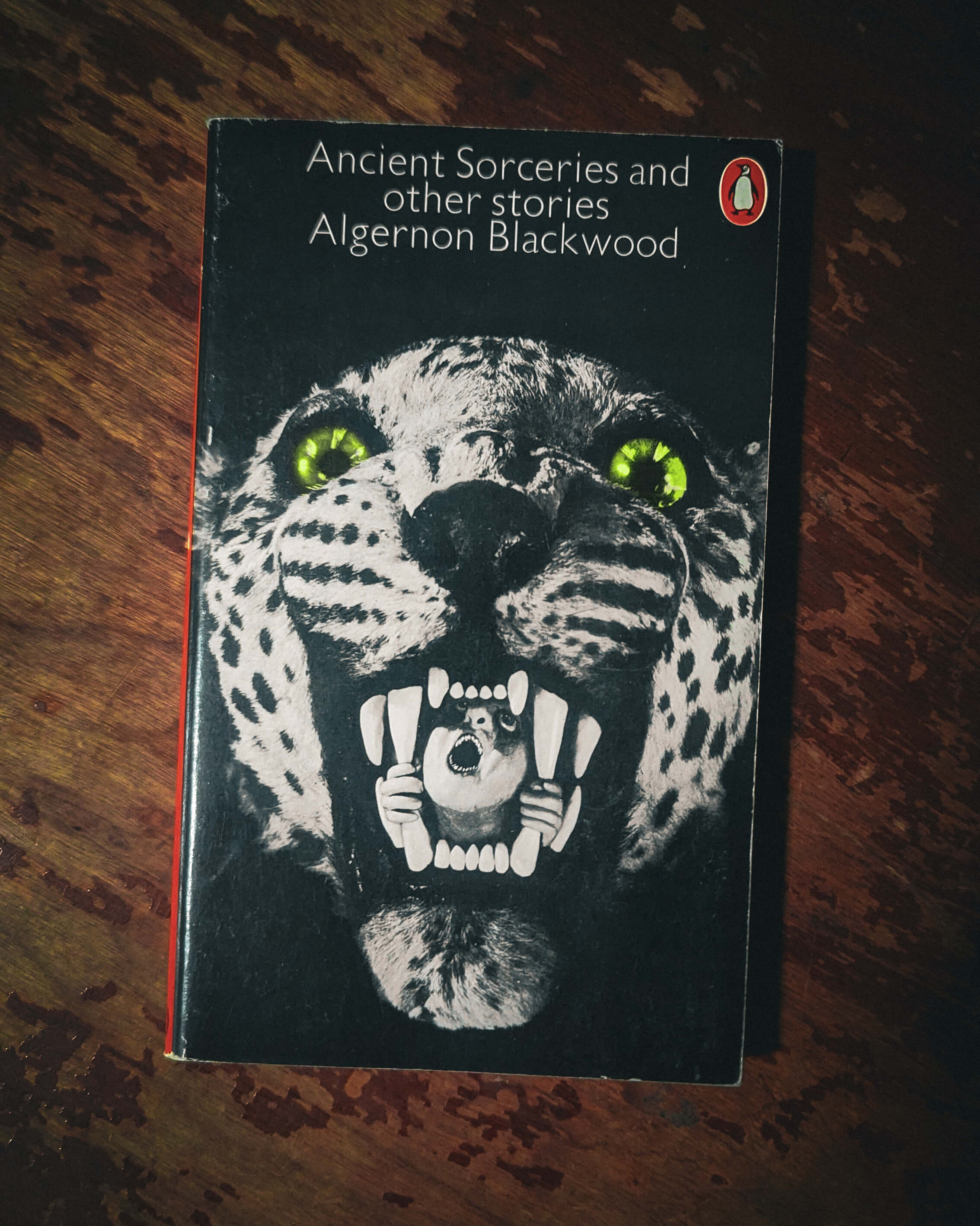

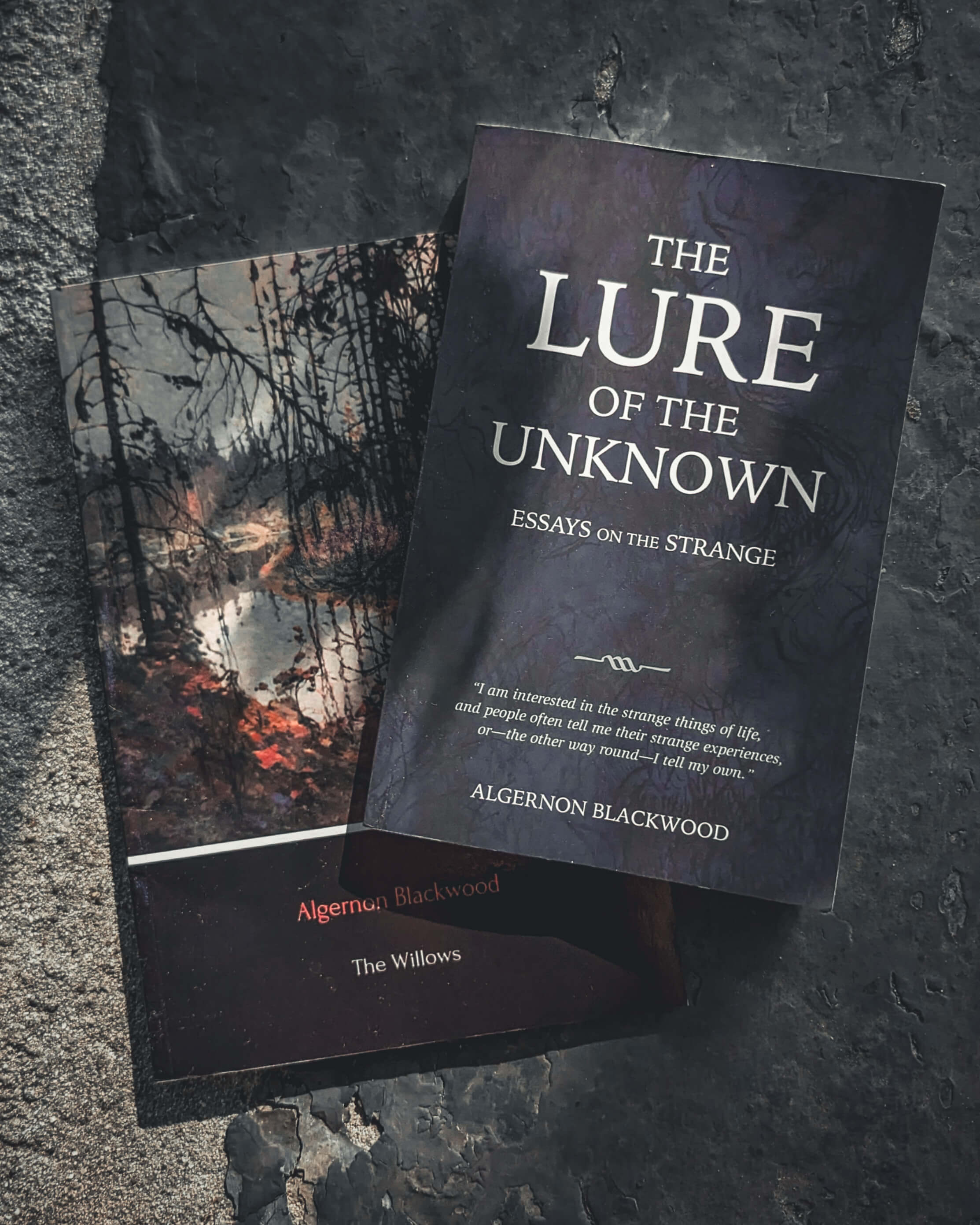

“The preliminaries are over; you have entered the Unknown.” — The Wendigo1

Hardly just ghost stories, Blackwood’s tales unfold around manifestations of unhuman dimensions that suggest “possibilities outside our normal range of consciousness.” Where Lovecraft’s horror is given eldritch geometry, Blackwood’s resists definitive form. The Willows presents a threat never clearly seen, mostly hallucinated, with a creeping sense that the land itself demands something in return for our trespassing. The Wendigo3 is not portrayed explicitly as an evil spirit, but the wilds themselves, a liminal zone where thought frays and language falters, stripping the mind of self and reason. In The Man Whom the Trees Loved, “love” is just the name we give to the motive of something that does not speak our language, an encroaching otherness that erases all human attachments.

Blackwood writes ruptures, not monsters. While his fiction draws on the conventional metaphysical categories of Romanticism, the occult and Gustav Fechner’s panpsychism, his best moments erode the limits of relation and representation. His personifications of the nonhuman are less assertions about its true nature than elaborations on how we impose meaning on the unknown through habitual patterns of thought. In destabilizing distinctions between inside and outside, self and other, he articulates a threat that is not simply an invasion from elsewhere but the recognition of a dark, impersonal nature already within. Horror lies in the loss of subjectivity to the opaque, bottomless depths of what exceeds us, evoked not just by the utter remoteness of alterity, but in its proximity and entanglement.

Cosmic estrangement resists reconciliation between the human and nonhuman, maintaining an ontological distance that preserves their irreducibility. It is exposure to alterity without assimilation or redemption, a revelation of mystery without meaning, what Eugene Thacker calls a “negative epiphany”4. There is no mastery over nature, no mystic communion with the universe, only encounter without relation. That is what keeps Blackwood’s Weird weird. It is the strange lure of the unknown once glimpsed beneath the stars in the Muskokas, where human presence is neither privileged nor required.

“Yet, ever at the back of his thoughts, lay that other aspect of the wilderness: the indifference to human life, the merciless spirit of desolation which took no note of man.” — The Wendigo

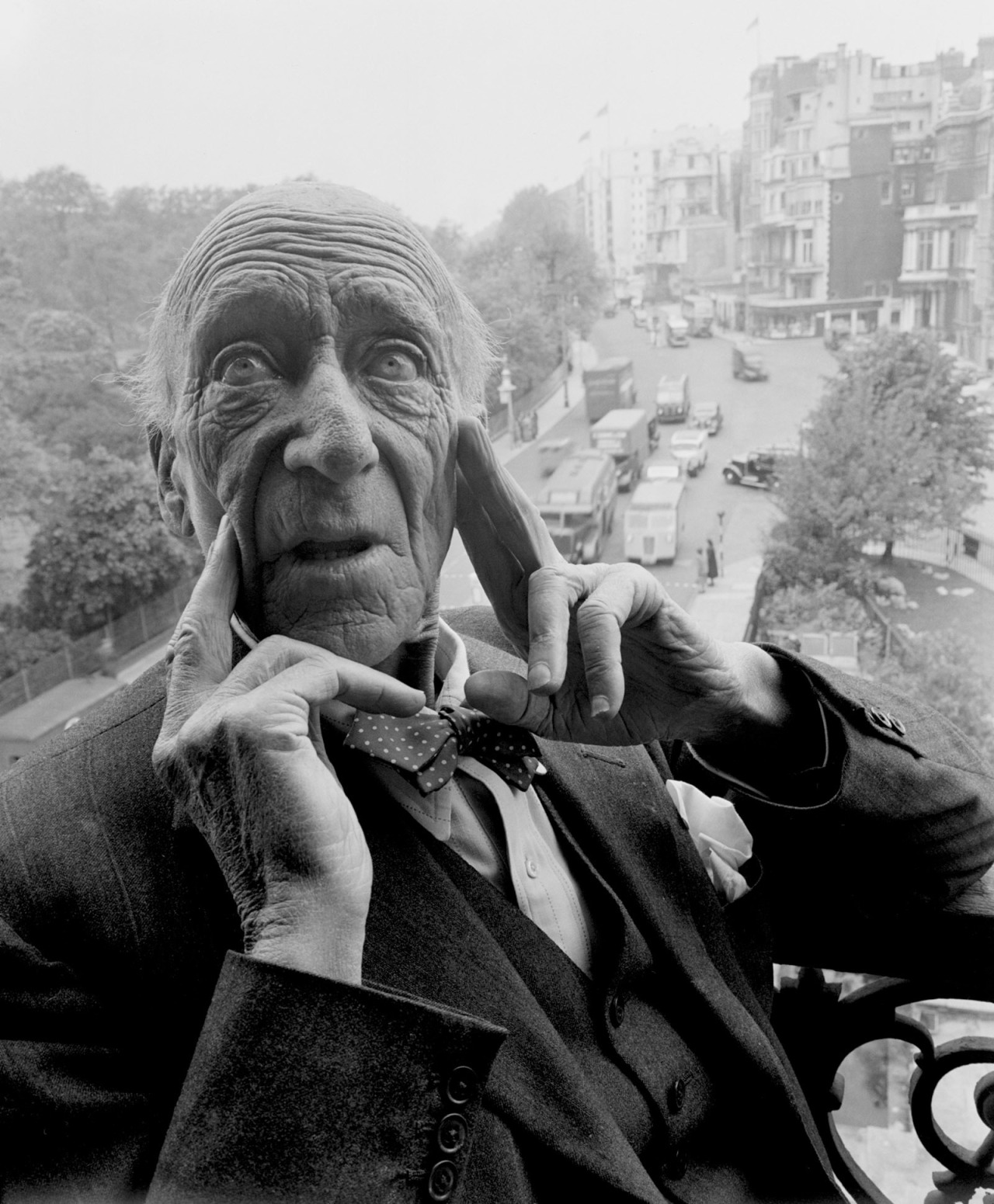

Algernon Henry Blackwood by Norman Parkinson, 1951.

Algernon Henry Blackwood by Norman Parkinson, 1951.

-

Blackwood, Algernon. “Best Ghost Stories of Algernon Blackwood”. Dover Publications, 1973. ↩ ↩2

-

Blackwood, Algernon. “Episodes Before Thirty”. London : Cassell, 1923. Link ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

Blackwood’s fiction bears the colonial biases of its time. As Newell point’s out: “[While] The Wendigo is something altogether more cosmic and unfathomable than a cheaply appropriated indigenous phantom … Blackwood’s racialised language can appear dated and problematic to modern readers: in several stories, including ‘The Wendigo’, he employs terms such as ‘red Indian’ and consistently associates indigenous characters with animality.” — Newell, Jonathan. “A Century of Weird Fiction, 1832-1937: Disgust, Metaphysics and the Aesthetics of Cosmic Horror”. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2020. For analysis on the misappropriation of the Wendigo myth in contemporary horror, see Johnson “A Creature Without a Cave” Link, and Nazare: “In retrospect, the disavowal of Native American language and literary tradition, the positing of the Native American as brooding bogeyman and howling, inarticulate fiend of the wilderness clearly served as a pretext and justification for cultural domination”. Nazare, J. (2000), ‘The Horror! The Horror? The appropriation, and reclamation, of Native American mythology’, Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts, 11 (1), 24–51 Link. ↩

-

Thacker, Eugene. “How Algernon Blackwood Turned Nature Into Sublime Horror”. Link ↩