Arcanum 17

“A shifty character dying of boredom in his absurd lands of treasure is fine for religion, and fine for little castratos, little poets and little mystic-mongrels. But nothing is ever changed by a great big soft strumpet armed with a gift-wrapped library of dreams.” —Georges Bataille, The Castrated Lion

Bataille worte The Castrated Lion in response to the second Surrealist Manifesto in 1929, expelled by the High Priest of Surrealism from his band of servile idealists. Bataille had such a wicked tongue. A final snip to the Castrated Lion.

From a young age, I was drawn to a 1969 paperback edition of the Manifestoes that sat on the family bookshelf somewhere between Freud, Jung, and the I Ching. Entranced by the psychic automatism that was Soluble Fish, with its hallucinatory words and strange typefaces on the cover (Anzeigen-Grotesk arranged by Quentin Fiore), I coveted it like some arcane spellbook, some incantations of which I can still recite from memory to this day:

“Watch out for

the fire that covers

THE PRAYER

of fair weatherTHE FIRST WHITE PAPER

Of CHANCE

Red will be.”

— Breton, The Surrealist Manifesto

Many Surrealists were expelled from the old boys club at some time or another by its Lion, André Breton. But Bataille, later in life, had ended Breton and the Surrealists for me. It was time to leave that nonsense of the occult behind; Bataille’s base materialism was the shit, so to speak. That said, I did not hesitate to investigate further when discovering, by pure chance, that Breton had stayed in Gaspésie, Quebec while in self-exile in late summer of that darkest of years, 1944. He would have been almost 50, devastated by the Second World War, divorced and estranged from his daughter, and now in his third marriage to Elisa, who had lost a child to drowning. This was a mature André with a lifetime of regret to reflect upon. And he had kept a journal, the lesser known Arcanum 17. So I brought it along, flipping through pages while gazing out across the cold, misty gulf of the St. Lawrence, following in the footsteps of Breton’s alchemical pilgrimage.

Melusine’s secret discovered, from Le Roman de Mélusine by Jean d’Arras, ca 1450–1500.

Melusine’s secret discovered, from Le Roman de Mélusine by Jean d’Arras, ca 1450–1500.

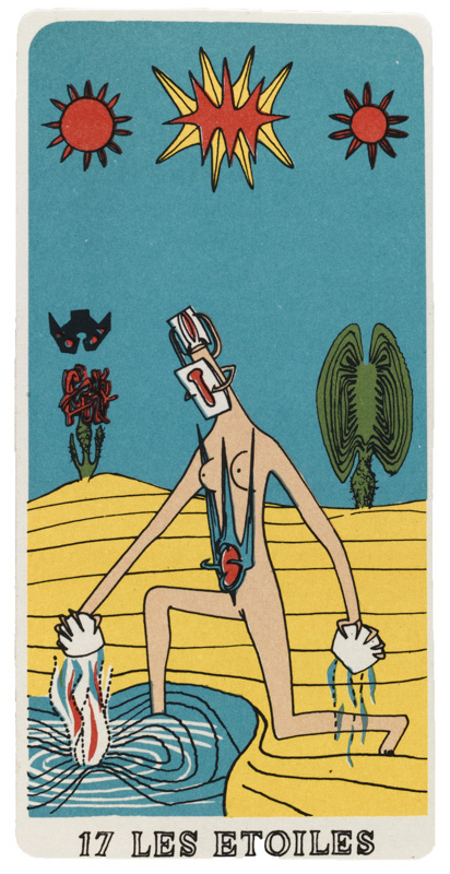

The 17th card in the Major Arcana is The Star. A woman kneels beneath eight stars, crowned by the North star, pouring water from two urns, one into a pool, another onto land, and a butterfly sits on a red rose. The card represents feminine qualities of creativity and transformation. A bridge between the material world and the soul, past and future, with the promise of new beginnings. Breton connected The Star with a complex figure of European folklore, Melusine. The tale has many variations, but it’s said Melusine was the cursed daughter of fay and mortal, a taboo coupling that often comes with a fatal condition. Every Saturday she secretly transformed into a monstrous hybrid with upper body of a beautiful woman and twin serpentine tails (depicted as either serpent or fish). She agreed to marry on condition her husband promise not to see her on said days, but driven by suspicion he spied on her, the taboo was broken, and she fled to lands in the West. As the legend of Melusine permeated the maritime sea-lore of the New World, she became a popular folk hero with judicial role as siren who punishes men who mistreat woman.

The story is tragic, loss without resolution, but one of endurance that became for Breton a hymn of hope in a time of suffering. “One must go to the depths of human sorrow, discover its strange capacities, in order to salute the similarly limitless gift that makes life worth living.”(Breton) Let’s not go so far as to praise him as a proto-feminist, but it is endearing to read words of an aging Breton at the end of the Second World War:

“Those of us in the arts must pronounce ourselves unequivocally against man and for woman, bring man down from a position of power which, it has been sufficiently demonstrated, he has misused, restore this power to the hands of woman, dismiss all of man’s pleas so long as woman has not yet succeeded in taking back her fair share of that power, not only in art but in life.” —André Breton, Arcanum 17

And so, it was the transformative tale of a mermaid, the surreal fusion of ordinary and extraordinary, that informed the alchemical poetics of Breton’s observations of Rocher Percé, the Philosopher’s stone.

photo of Percé Rock by beingcompiled (2021)

photo of Percé Rock by beingcompiled (2021)

“In everything one treads on, there is something that comes from so much farther back than mankind and which is also going so much farther.” wrote Breton. In the primordial magmatic and metamorphic processes of geological forms, Breton saw what resembled the cyclical rhythms of desire and the unconscious that surge through human history like a slow eruption. “Convulsive beauty will be veiled-erotic, fixed-explosive, magic-circumstantial, or it will not be.”(Breton) Exemplary of the “fixed-explosive of convulsive beauty” were crystalline structures, wherein the eternal tensions of order and disorder, movement and stasis, attraction and repulsion, seemed to magically reconcile, silently frozen in time. Crystals reflected the underlying neural symmetries of the mind, revealed through the generative patterns of psychic automatism. This wasn’t mere symbol or metaphor, but thought itself, latent in material form, a surreal dissolution of subject-object duality, conduit between our inner psyche and an outer world that dreams. Crystallomantic modes held transformative wisdom that could be meditated on and communed with, like reagents in an alchemist’s laboratory. Interior metamorphosis through exterior visual transmutation, a “visionary mineralogy”.

The fabled catalyst of alchemical transmutation was the Philosophers’ stone, a panacea said to cure all ills and bestow eternal youth. Perhaps Breton’s magnum opus was the search for this stone, which led to the rock at Percé. “A marvelous moonstone iceberg,” he called it, “the mother of all crystals.”(Breton)

Having served in the psychiatric wards of the medical corps, Breton was intimately familiar with, if not traumatized by, the atrocities of war. Like The Star and the myth of Melusine, he took solace in the rock’s conciliation of dialectical opposites - impermanent yet fixed, metamorphosing into hallucinatory geometries slowly shaped over time by the raging storms of the sea. Geological time taught that, despite temporary asymmetric disruptions, consistent stratigraphies endured. Yet nothing is permanent. Love, poetry, art could transform anguish into ecstasy, weapons far greater than party politics for combating the violent fragmentation of the modern world.

“It’s as if the vessel, just a short while ago bereft of riggings, seems suddenly to be equipped for the most vertiginous of ocean voyages … [Its slow erosion and weathering] has the virtue of setting the enormous vessel in motion, of providing it with motors whose power is comparable to the very slow and yet very noticeable process of disintegration that it’s undergoing. It’s beautiful, it’s moving that its longevity is not limitless and at the same time that it covers such a succession of human lives. In its depths there is more than enough time to see born and die a city like Paris where gun shots are reverberating right now even inside Notre Dame as the great rose window turns. And now that great rose window whirls and twirls in the rock: without a doubt these shots were the prearranged signal because the curtain is rising.” —André Breton, Arcanum 17

photo of Percé Rock by beingcompiled (2021)

photo of Percé Rock by beingcompiled (2021)

“To describe the geometry of an era that has not yet come full circle requires an appeal to an ideal observer, removed from the contingencies of that era, which implies from the start the need for an ideal observation post … no place fulfills the necessary requirements as well as Percé Rock, as it unfolds to me at certain times of day. It’s when, at nightfall or on certain foggy mornings, the details of its structure become cloudy that the image of a sloop, always imperiously commanded, can be refined from it. Aboard, everything points to the infallible glance of the captain, but a captain who would also be a magician.” —André Breton, Arcanum 17

Perched from his hermetic observation post, the magician peers into the folds of Percé Rock like a scrying stone. A heavy curtain lifts in the fog to reveal a surreal, mythopoetic theatre. What follows is a confused collage of current events, arcane knowledge, mythic history, personal experience. Who knows which of many experimental techniques were employed in writing 17, but it rambles like a somnambulist at twilit, disjunctive imagery scatters like crystal dendrites. Three unifying elements barely keep the parlor trick from failing completely: poetry, liberty, love. The writing is fragile, but these moments endure, which, in the end, was the very beauty he saw in the rock.

“It has been claimed that, faced with Percé Rock, the pen and the brush must admit their impotence and it’s true that those who are called upon to speak least superficially about it will think they have said it all when they have attested to the magnificence of this curtain, when their voices suddenly deepened to depict its dark radiance, when they have succeeded in creating some order out of the modulation of the mass of air that vibrates in its majestically discordant pipes. But, lacking the knowledge that it’s a curtain, how could they suspect that its staggering drapery hides a set with many levels?” —André Breton, Arcanum 17

photo of Percé Rock by beingcompiled (2021)

photo of Percé Rock by beingcompiled (2021)

“On a revolving stage, a chain of white elephants fold their legs in rhythm with the wind and the seas in order to make the moons in their toenails turn with the beat, brandishing their trunks at the sky, generating with their imperceptible sway alone the now transparent image of the rock. Where just a while ago one could only see serpentine bands of quartz, the trunks in their turn are lost in the diffused light, giving way to a thousand heralds carrying streamers who scatter in all directions … In these bright ship flags fringed with gold, no one would think of recognizing all the coarse material that was hoisted and is still being hoisted above the risky undertakings of mankind. And yet it’s the great swell of those banners, dominated, as we’ve seen, by the rejection of the jolly roger and subject to a dazzling transmutation, which takes hold of the rock to the point of seeming to make up its whole substance. And the proclamation, trumpeted to the four winds, is in fact important since the shouts of beaming mouths trimmed with shot silk echo in every direction only the eternal newsflash: the terrible curse has been lifted, all power for the regeneration of the world lies in human love.” —André Breton, Arcanum 17

In the wake of two world wars, Breton was in search of a new mythology, and fancied himself a visionary. He believed, naively perhaps, in the power of literature to effect social transformation. Without understanding our innermost dreams, changes to social or economic structure would only produce new forms of alienation. Meanwhile, maybe the myths that were needed had been here all along, but were silenced. The stories of the Mi’kmaq elders of the maritime provinces who call Gaspésie home aren’t so easy to find (at least for the casual tourist like me, I tried), but surely they could have taught the bougie lion of Paris art salons a few hard lessons about rocks, let alone visions, and the sad beauty of impermanence.

A “mystic-mongrel” with a “gift-wrapped library of dreams” wrote Bataille. But I like to believe in that which endures in Arcanum 17, a turn to lesser known narratives, the occult and indigenous knowledge, as a sincere search for healing. A beguiling landscape writing that flows unimpeded between naturalistic observation and dream, that looks to nature, geology and the non-human for wisdom. For Breton, poetry was “a state of mind that encompasses all writing resulting from the passionate embrace of all entities human, animal, plant and mineral that constitute the network of this earth.”(Breton)

“André Breton was a lover of love in a world who believes in prostitution.” —Marcel Duchamp

photo of Percé Rock by beingcompiled (2021)

photo of Percé Rock by beingcompiled (2021)

“This may be a mere drop in the ocean, but nevertheless it leads directly to the hermetic concept of living fire, the philosopher’s fire. The secret of its attraction and its lasting quality surely lies in the fact that, under a great weight of shadow, the image of ‘universal sperm’ circulates through it, enhanced by its very multiplicity … Yet that ark remains, and even if I can’t make everyone see it, it’s filled with all the fragility but also with all the magnificence of human genius. Set in its marvelous moonstone iceberg, it’s driven by three glass helices which are love, but as it arises invulnerably between two beings; art, but art arrived at its highest point; and the all-out struggle for freedom. Observed more absentmindedly from the shore, Percé Rock only has wings because of its birds.” —André Breton, Arcanum 17