Bread & Puppet

Peter Schumann’s family fled their home in Silesia, Germany during allied bombings in World War II. Living in a refugee camp, they survived on turnips and his mother’s sourdough rye bread. It was a life lesson in the terrors of war that, Peter points out, is a reality many North Americans have never experienced. Elka Schumann, born in Magnitogorsk to a Russian mother and American father — a radical journalist critical of Stalin — remembers living under constant fear of German bombings. Elka and Peter met in Munich when she was a student and he was in hospital with a head injury from a bicycle accident during a recruitment stunt for his experimental dance troupe. Based in a small village outside Munich, in an old medieval domicile for priests, the troupe would tour Germany showcasing their dance and woodcuts.

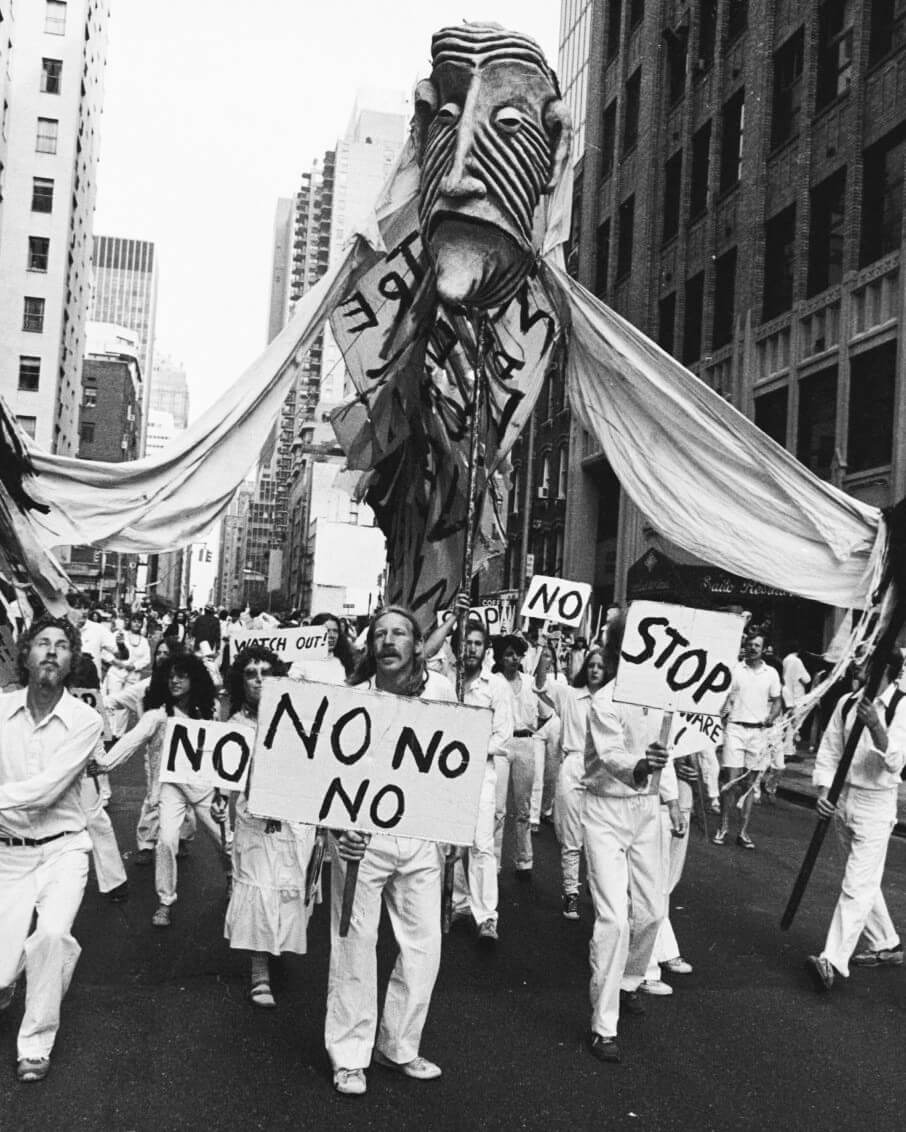

After meeting John Cage and Merce Cunningham, and inspired by the post-war avant-garde, Peter and Elka moved with their children to Manhattan’s Lower East Side in 1961. They began contributing their theatrical flair to street parades and protests advocating for the labour movement and against poor housing conditions, nuclear proliferation and the Vietnam War. Towering puppets crafted from papier-mâché, burlap and twine, alongside costumed caricatures marching on stilts were hard not to notice and made the radical political message less confrontational for the police and more sympathetic to the general public. What also made for a better audience, Peter found, was when, instead of chattering amongst themselves, they were chewing on his homemade bread — the same recipe his mother used during the war. At that time, the phenomenon of nutritionless Wonder bread had swept through America, and wimpy bread is an atrocity intolerable to any proper German. In combining food and theater, blending the practical with the spectacular, taking art out of affluent institutions and into the streets where it could make a difference, Peter discovered a recipe that would sustain the hearts of audiences for years to come. In 1963, Bread and Puppet theater was officially founded.

Bread and Puppet Theater performs during a protest in New York in June 1982. AP

Bread and Puppet Theater performs during a protest in New York in June 1982. AP

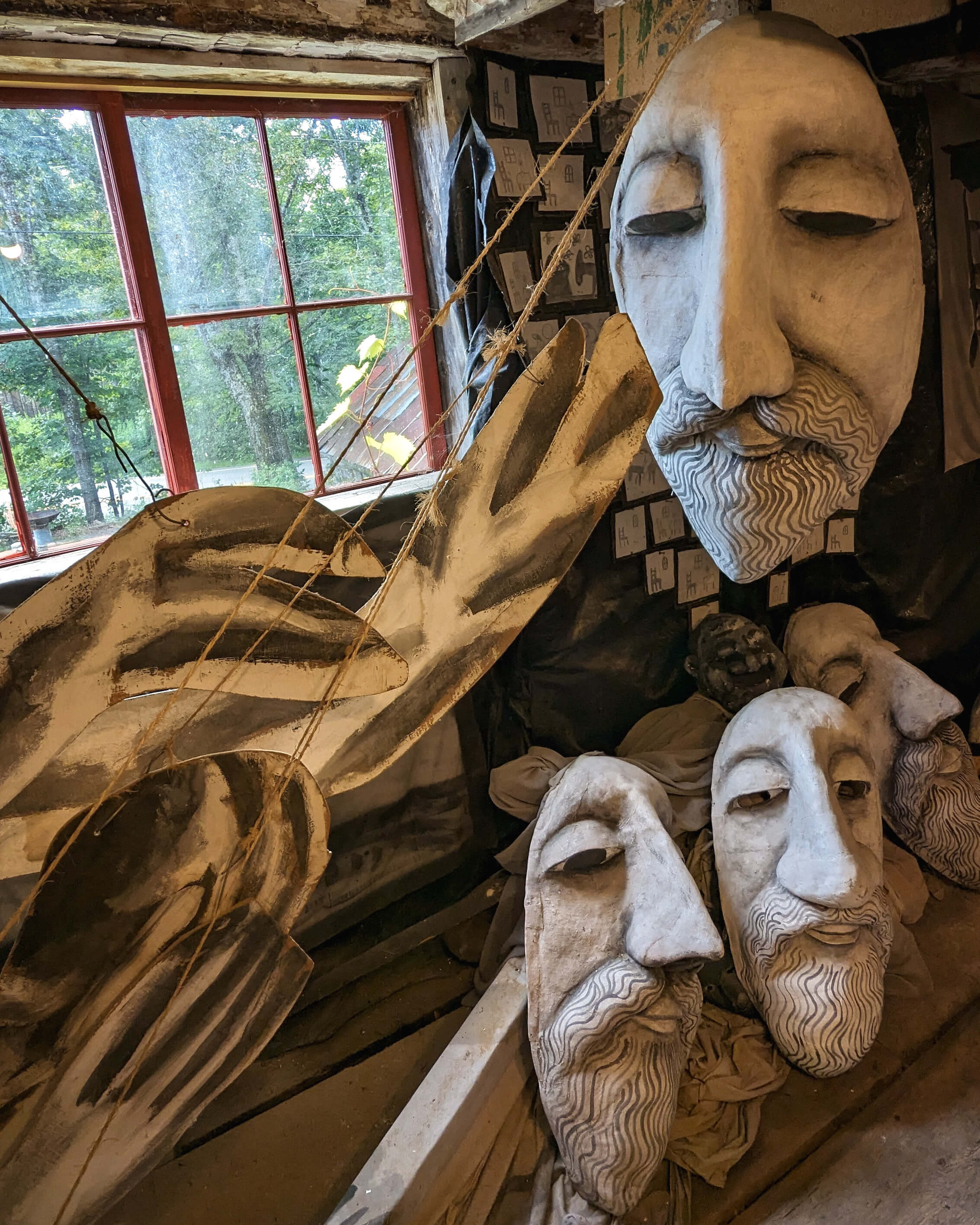

In the 70s, Elka and Peter joined Goddard College and B&P moved to Vermont. Peter composed his inaugural “Domestic Resurrection Circus”, employing theater as an everyday means to counter political apathy and commercialism. It became a summer tradition, drawing puppeteers, dancers and activists worldwide. In the 90s, B&P found its current home in the Northeast Kingdom on farmland bought by Elka’s family. When Peter first surveyed the property, he envisioned the gravel quarry being dug for highway 91 as a natural amphitheater, crowned with majestic pines, perfect for pageants and circuses. Ever since, the Schumanns have housed the puppets crafted each year in a historic barn built by Shakers in 1865.

Spoiler alert. Entering B&P Museum is like ascending into some heavenly firmament of puppetry. A pantheon of mythical deities, saints and demons of our collective dreams and nightmares, everyday folks, freaks and ghosts from American history, loom larger than life, quietly poised in a vast diorama extending from creaky floorboards into the pitched roof above. Every nook and cranny brims with whimsy, each puppet having exhausted its debut in a once epic performance yet ready to spring to life at any moment to tell new tales. The space is reminiscent of the obsessive figuration and celebration of excess in Renaissance art and the grotesques of Gothic cathedrals. Elka once mused that Peter is gripped by horror vacui and abhors any empty space that could be filled with creativity. It isn’t just some barn full of dusty old puppets, but the combined visionary genius of all the artists that have contributed to the theater under Peter’s direction for 60 years.

It’s something everyone should experience firsthand. I’m torn about sharing photos of it at all. I sat by the entrance, listening to reactions as people stepped through the barn doors, which ranged from stupefied remarks like, “Why do they all look so miserable?” by those sadly too disneyfied by pop culture to get it, to those suddenly moved to tears. I was of the latter, as moved by it as any cathedral or temple, especially its legacy as a genuine collective effort to bring joy and change into the world.

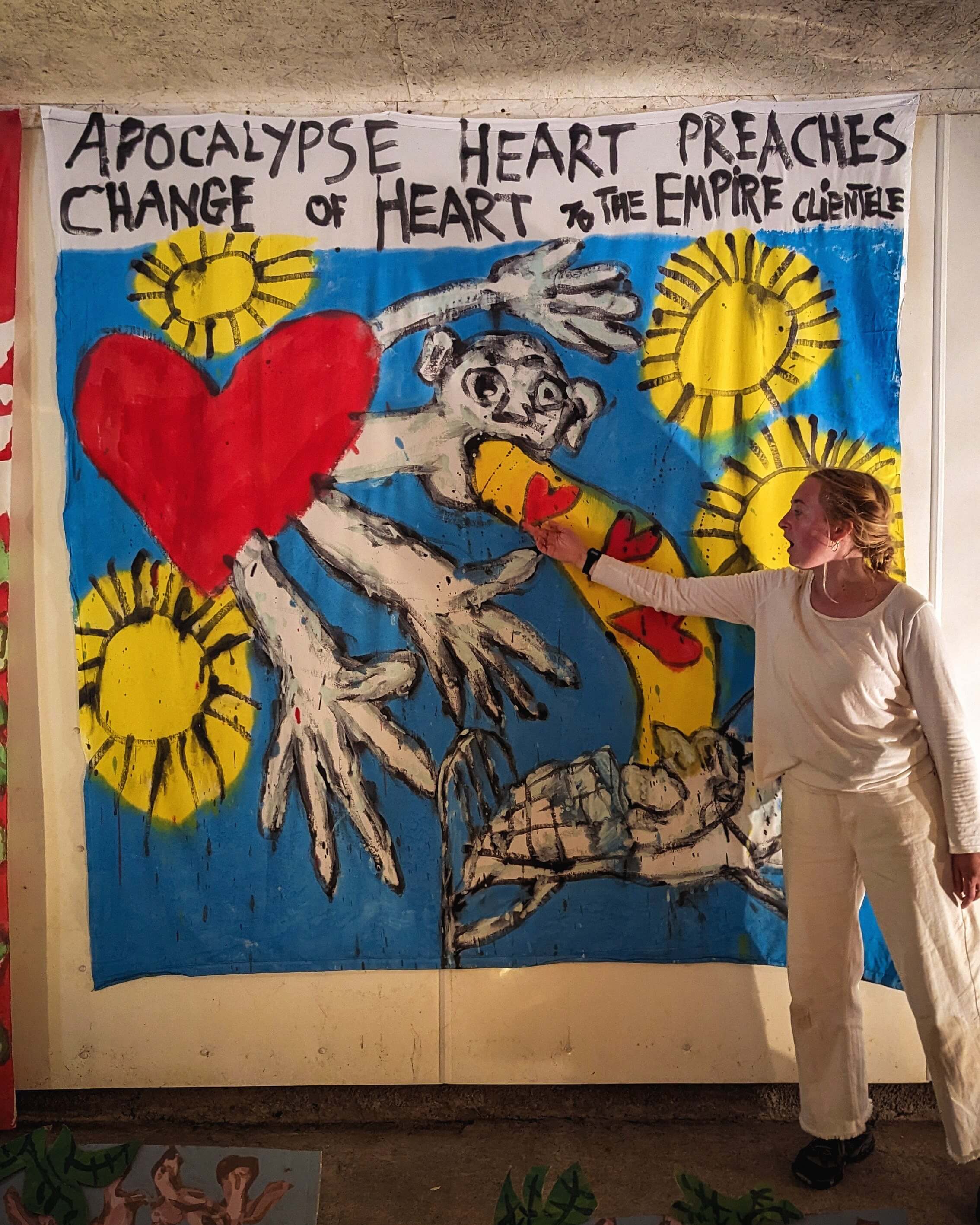

The philosophy behind B&P’s “WHY CHEAP ART? manifesto” is the democratization of art, repurposing cheap materials to create aesthetically striking, politically powerful art that’s affordable and accessible to everyone. Puppeteer Josh Krugman calls it “Possibilitarianism”, exploring the many alternatives to the destructive and wasteful machinations of Capitalist empire. As a puppeteer, one picks up an everyday object and asks what its possibilities are, not just its potential to tell a story, to be beautiful or even spiritual, but practical uses beyond those dictated by the market, including how it can be discarded or reused. This simple meditation is how we ought to think everyday, socially and economically, and how we might improvise with the debris left to us for collaborative survival in economic and ecological ruin.

B&P’s political statements don’t sit well with everyone. Recently, some community members disagree with Peter’s criticism of NATO involvement in Russia’s war on Ukraine. “It’s puppetry, not preaching” says Peter, who has spent a lifetime opposing American exceptionalism, profiteering and warmongering. B&P has acted like an inner conscience for some Americans to reflect on their own complacency or involvement in America’s role on the world stage. Theater can be a public space to ruminate on controversial ideas while mitigating confrontation. Humour, absurdity, and abstraction of the carnivalesque leavens contentious subject matter and renders it more palatable. By participating virtually in, e.g. the ritual burial of the gun, one tunes into a collective thinking that entertains the possibility of actual transformation. B&P’s power to attract thousands and the overwhelming response of its audience is proof there’s hunger and gratitude for this work. In a world lacking collective rituals that connect us to anything greater than our everyday routines of consumption and accumulation, it is precious and needed.

The spirit of laughter “frees human consciousness, thought, and imagination for new potentialities. For this reason, great changes … are always preceded by a certain carnival consciousness that prepares the way.” ― Bakhtin

B&P shows are ever-evolving. Each year, Peter sets a theme and puppeteers propose sketches centered around global crises and collectively critique them. As they tour throughout the off-season, performances remain relevant as the troupe continuously improvise and adapt to current events.

“Praise to the dirt which is our mother. And gives us life together with sister and brother. We must be alert, to keep her from getting hurt. By all the shit and the bother. Praise to the dirt which we call our life. And is our joy and is not our strife. And what is our goddamn calamity. Which is our idiot system Deprived of beauty and wisdom.”

B&P’s ethos is both unabashedly utopian and deeply pragmatic, inspired by Kropotkin’s Anarchist Communism. Mutual Aid is a model of social organization based on scientific observation that cooperation and reciprocity found naturally in human and animal communities is more prevalent and pragmatically advantageous for survival than the adversarial “survival of the fittest” endorsed by Social Darwinists. Far from a natural given, Capitalism elevates competition in the name of innovation as justification for exploitation, resource hoarding and class domination. Kropotkin advocated flattening social hierarchies in favour of collective consensus where all participating members are empowered to take responsibility and enact change. As one of America’s longest-standing, nonprofit, collaborative theater companies, B&P isn’t just an alternative vision to Capitalism but a real-world example actually being practiced, a “domestic insurrection” experimenting with social, political and ecological transformation in everyday life, where art and bread feed both body and soul.

“Resistance of the heart against business as usual” - B&P

Hurrah! Utopian projects should be celebrated for what they are, as possibilities, an effort, at the very least, to imagine alternatives to be further experimented with and amplified. Those who might ridicule it as hippy utopianism should ask themselves what is truly naive and ideologically radicalized in the face of very real and imminent ecological apocalypse: the belief we can just carry on with business as usual.

[This is our] “response to our totally unresurrected capitalist situation … our culture’s unwillingness to recognize Mother Earth’s revolt against our civilization. Since we earthlings do not live up to our earthling obligations, we need resurrection circuses to yell against our own stupidity.” — B&P

Utopias are more journey than destination. As B&P surged in popularity in the late 90s, large crowds were drawn to unsupervised after-parties. Tragically, one rowdy confrontation resulted in death, ending the Domestic Resurrection Circus for many years. Thankfully, despite Elka passing away in the summer of 2021 and Peter suffering a stroke, B&P has found the heart to carry on.

As the “Heart of the Matter Circus” ends for the day, a pageant of puppeteers ushers the audience up the slope of the ampitheatre into the surrounding fields above. Puppeteers clad in white circle a maypole with flowing ribbons, singing “In the meadows dressed in green, there he’s seen”. Each pageant begins with “Through All the World Below”, an anonymous hymn celebrating God’s presence as evident in nature. The puppet cult vibes are more endearing than creepy. It’s like stepping into the travelling puppet show of Russell Hoban’s post-apocalyptic classic, Riddley Walker. A few of the puppeteers lift a tall ladder straight up into the sky, suspended by ropes, which Peter ascends, as if in a game of trust. From the top, he surveys the fields before them, directing puppeeters into various positions based on falling sunlight and shapes cast by the shadows of tall pines. A quartet performs a Beethoven fugue. Figures on enormous stilts in the far distance wave long flags, drawing attention to billowing storm clouds. Giant puppet hands draped in translucent cloth manoeuvre against the horizon, pointing to the sky.

“The real spectacle isn’t the puppetry, it’s the sky. But you animate underneath it sufficiently so people realize that. All of a sudden, what the light does to these things becomes most important, and people get that. They sit there and all of a sudden the cloud bursts open, or goes away and the clear sky comes underneath, these are the real events.” — Peter Schumann 🥀

- Note: The history Bread & Puppet Theatre is pieced together from online research, not any first hand account from the Schumanns themselves.