Rabelais and His World (1 of 2)

“Ignorance is the mother of all evil.” ― François Rabelais, Book IV

Giants of “Par Ris”

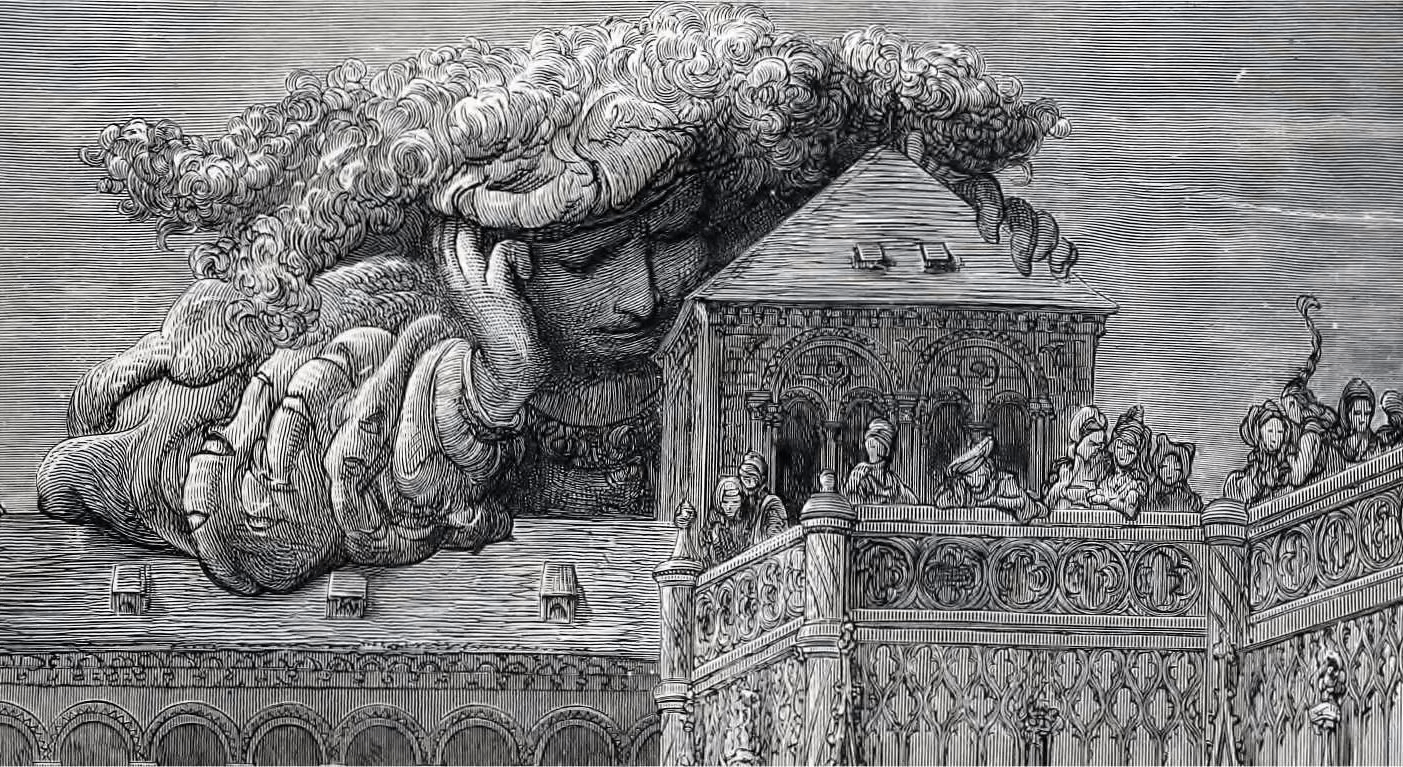

Before François Rabelais (c. 1494-1553) immortalized Gargantua in “La vie très horrifique du grand Gargantua” (16th c.), the gluttonous giant had loomed large in the landscapes of medieval folklore. Legends spoke of basins formed by his enormous footprints, of rivers that gushed forth from his urine, and mountains shaped from his dung. Everywhere, the dismembered and scattered body of the giant —or personal belongings dropped from his basket— could be found in the toponymy and natural features of the landscape. A great number of rocks, stones, megaliths, dolmens, and menhirs bore his name: Gargantua’s finger, tooth, cup, armchair, stick.1 Women seeking husbands or motherhood would rub against Gargantua standing stones, inspired by his prodigious phallus that was in proportion to his vast size. Some believed he was Gargan, the ancient Gallic demiurge, a colossal yet benevolent force that bestowed order on an otherwise chaotic and inexplicable world.2

Spoken accounts of giants were collected in chapbooks —notably “Les Grandes Chroniques du Grand et Énorme Géant Gargantua” (1532)— and distributed by traveling peddlers in the marketplaces across France during the turmoil of the Reformation. Rooted in the land and the shared vernacular and folk humor of its people, these larger-than-life stories provided the raw material from which Rabelais would craft his great satirical allegories.[^3] When studying Greek language as a monk in 1523, the Sorbonne had confiscated Rabelais’ books, deeming them a threat for encouraging freedom of thought and heresy. Writing under various pseudonyms, Rabelais employed wit and satire against medieval scholasticism and the restrictive influence of the monarchy and Catholic Church on intellectual life.

The Good Giant, from ‘Gargantua’ by Francois Rabelais (1494-1553) reproduction of 1532 edition

The Good Giant, from ‘Gargantua’ by Francois Rabelais (1494-1553) reproduction of 1532 edition

Rabelais’ giants embodied boundless, irrepressible appetite — both literal and intellectual — serving as exaggerated symbols of human excess, folly, and insatiable curiosity. In the story of Gargantua’s arrival to Paris, Gargantua is so pestered by the simpletons of the city he climbs the towers of Notre-Dame and pretends to offer them wine as a gesture of goodwill. Purely for his own amusement, he undoes his codpiece and drowns them in his urine, baptizing the city with its new name, “par ris” (by laughter). The more serious passages celebrated humanist ideas emerging in the Renaissance at that time, advocating for a society enriched by individuals with broad education and intellectual freedom rooted in strong moral foundations. When the giant Pantagruel is sent to Paris for education, he receives a letter from his father, Gargantua, encouraging the young giant to embrace the many learning opportunities that had been absent in his father’s time:

[T]he times were not as fit and favourable for learning as they are today, and I had no supply of tutors such as you have. Indeed the times were still dark, and mankind was perpetually reminded of the miseries and disasters wrought by those Goths who had destroyed all sound scholarship … As you may well suppose, Pantagruel studied very hard. For he had a double-sized intelligence and a memory equal in capacity to the measure of twelve skins and twelve casks of oil.3

Centuries later, Russian philosopher and literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin (1895–1975) saw Rabelais’ time as one that paralleled his own — a historical moment of revolutionary potential under Stalin’s brutal totalitarian. An oppressive authority bore down from above, while from below, a new world struggled to be born.

The principle of laughter and the carnival spirit on which grotesque is based destroys this limited seriousness and all pretense of an extra- temporal meaning and unconditional value of necessity. It frees human consciousness, thought, and imagination for new potentialities.1

Bakhtin defined the role of the intelligentsia as those who interpret the world for society, a task made especially difficult during periods of upheaval like Russia’s 1917 revolution. In such moments, artists and intellectuals could no longer remain detached observers but were instead forced, along with all social classes, to actively participate in history. Rabelais’ narratives, drawn from folklore and popular language —earthy, sensuous, irreverent— offered a model that liberated readers from the ideological grip of official discourse. With their unrestrained appetites and unchecked laughter, the giants embodied a vital, libidinal energy that endlessly exceeded the manufactured mythology of Soviet Socialist Realism, which imposed ideological and aesthetic uniformity through idealized depictions of workers and model citizens that failed to capture the sometimes crude and untamed nature of who the people really were. This was literature in upward defiance of authority, a grounded stance from which to laugh in the face of lofty state idols. For Bakhtin, as for Rabelais, laughter and subversion were essential to intellectual and political freedom —a reminder that wherever authority seeks to fabricate truth, other voices will rise from below to mock, to question, to undo.

“No dogma, no authoritarianism, no narrow-minded seriousness can coexist with Rabelaisian images; these images are opposed to all that is finished and polished; to all pomposity, to every ready-made solution in the sphere of thought and world outlook.”1

The Carnivalesque

Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1559)

Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1559)

The key to understanding Rabelais’ subversive power, Bakhtin claimed, was the carnivalesque, festivities and rituals rooted in peasant traditions that temporarily dissolved social order, when eccentric and inappropriate behaviors, ordinarily deemed unacceptable, were not only permitted but encouraged. Accepted binaries were turned upside down or inside out -heaven and hell, sacred and profane, sense and nonsense— allowing for the expression of alterity and the free parodying of authority without fear of reprisal.

A popular theme was the mock crowning and subsequent de-crowning of a carnival king. But rather than a simple inversion of power, carnival eradicated social distance, creating a deeply participatory and regenerative act of communal creativity. Whether kings or beggars, clergy or commoners, fools or intellectuals, all members of society took part. Although rulers and institutions licensed or regulated carnival, its true sanction came not from a calendar prescribed by church or state but from a more ancient and powerful force of the people to which even priests and kings ultimately deferred.

Unlike satire or modern irony, which can be detached or cynical, carnival laughter was not merely critique but a joyous act that liberated and renewed rather than simply destroyed. The carnivalesque was not limited to specific events; it was, rather, a state of mind, a way of understanding of the world that permeated all aspects of life, thriving on contradiction, multiplicity, and ambiguity, celebrating the process of change itself. Like Bakhtin’s understanding of dialogue — that meaning is never singular but emerges through a polyphony of competing voices — carnival resists ideological closure. Its laughter is never final but always open-ended, shaped by competing perspectives, each undermining the authority of the last. By resisting and exceeding closure and finality, the carnivalesque, Bakhtin argued, was inherently opposed to totalitarianism.

As opposed to the official feast, one might say that carnival celebrated temporary liberation from the prevailing truth and from the established order; it marked the suspension of all hierarchical rank, privileges, norms, and prohibitions. Carnival was the true feast of time, the feast of becoming, change, and renewal. It was hostile to-all that was immortalized and completed. 1

The Grotesque

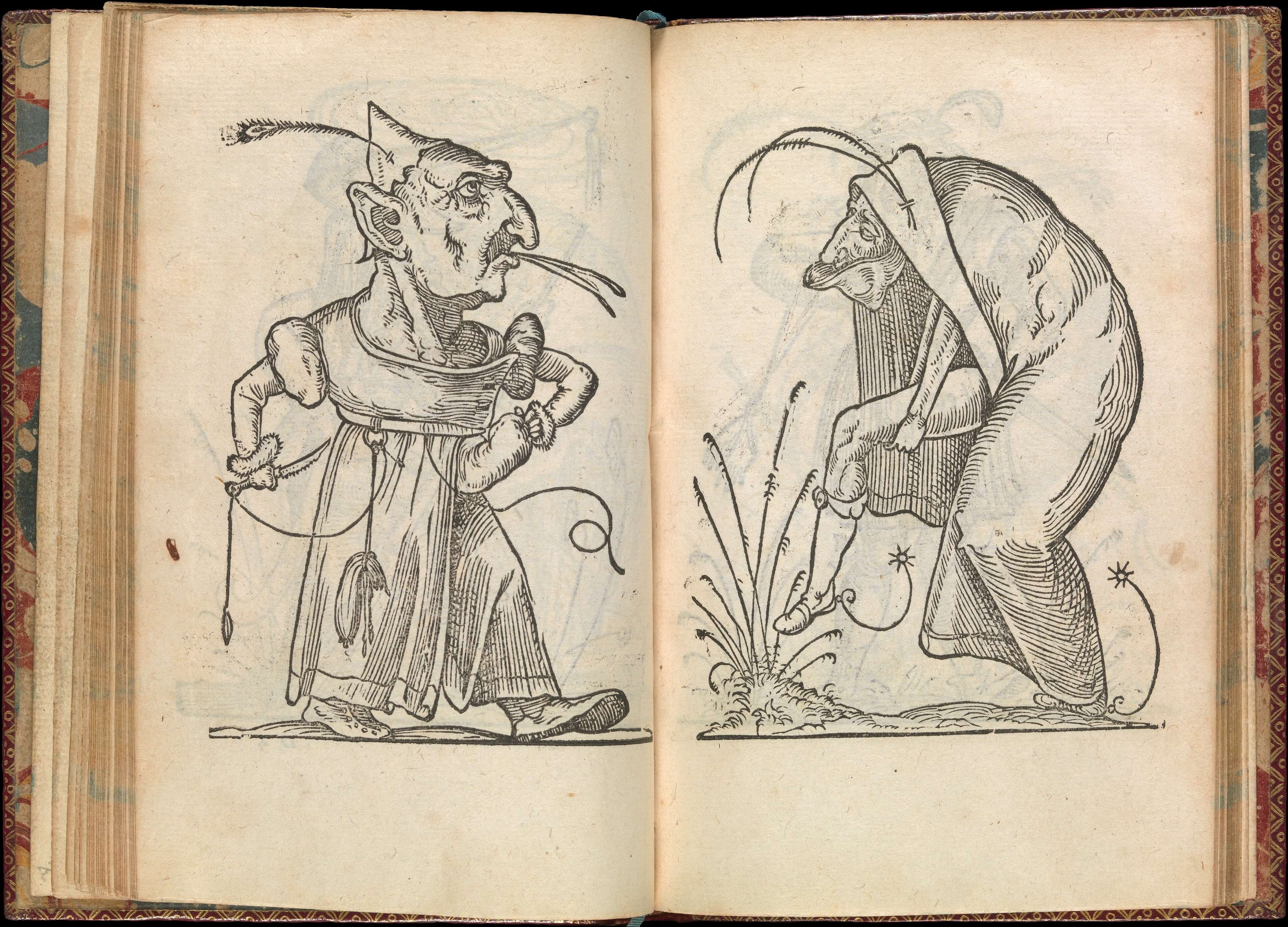

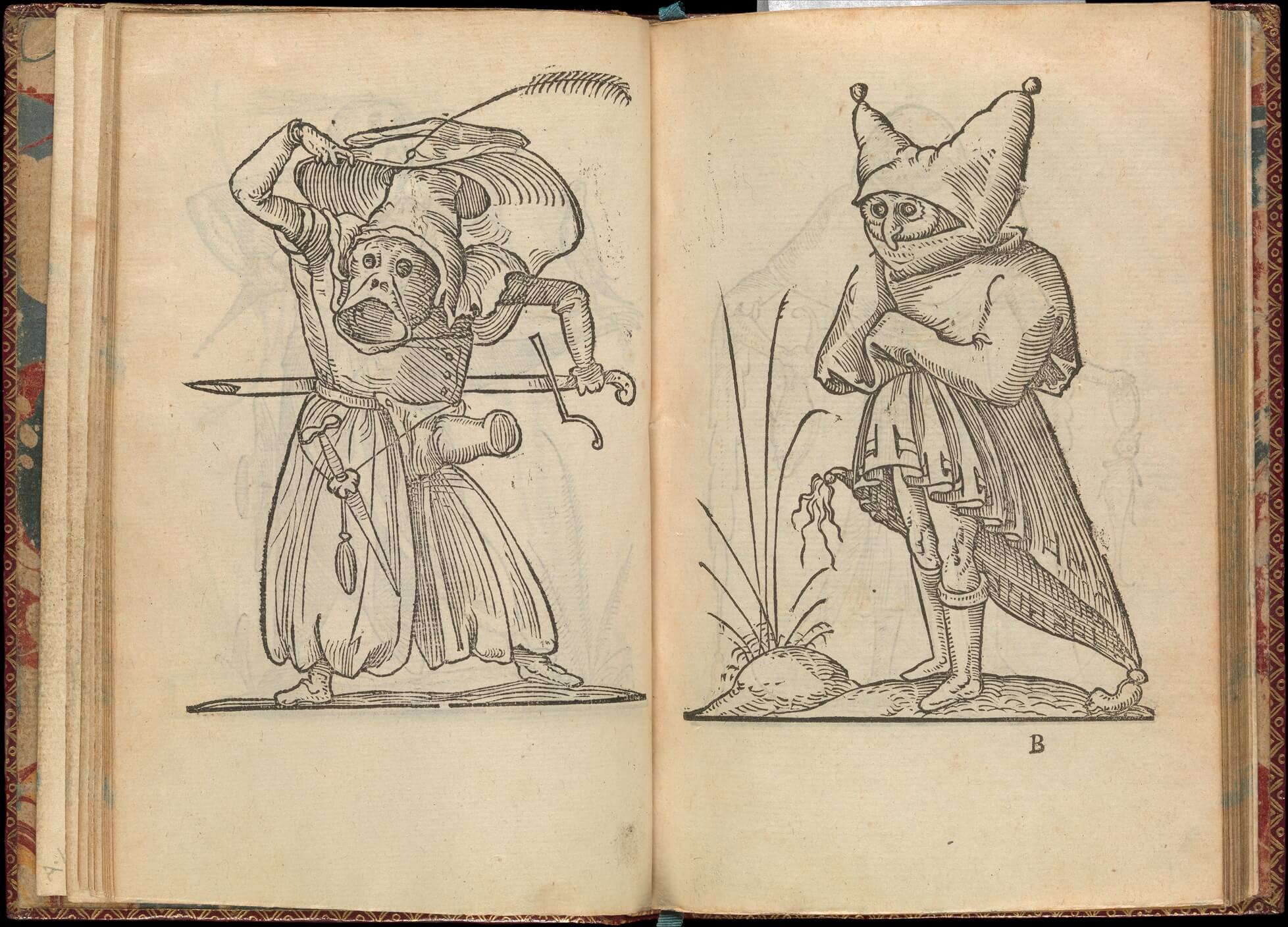

“The Drolatic Dreams of Pantagruel”, 1565, published by Richard Breton

“The Drolatic Dreams of Pantagruel”, 1565, published by Richard Breton

Published after Rabelais’ death in 1565 by Richard Breton, “The Drolatic Dreams of Pantagruel” contains 120 woodcuts -widely credited to artist François Desprez- depicting the bizarre inhabitants of Rabelais’ world. The title’s archaic term “drolatic” (from French drolatique, “humorous”) suggests these caricatures emerged from the dreams of Pantagruel himself. While echoing the surreal beings found in early medieval masters like Bruegel and Bosch, the images most resemble drolleries — small, often whimsical marginalia in illuminated manuscripts depicting humans, animals, or hybrids of the two, frequently in battle.4

The woodcuts present a hodgepodge procession of absurd figures with incongruous bodies, both ludicrous and disturbing. Some are draped in ecclesiastical garb with broad brimmed hats and ghastly flowing robes that exaggerate authority. Some parade about in makeshift armour with ostentatious spurs and weaponry, signaling aristocratic lineage. Others flaunt musical instruments or prolific codpieces like crude overcompensation for lacking masculine virtues. Among them, a figure clad in a cardinal’s cassock casts a book into the depths of a well, suggesting censorship. There is often no clear delineation between where one thing begins and another ends, whether human or beast, anatomy or object. The grotesque beings mimic and mock their way through a world turned upside down in a parody of power.

“The Drolatic Dreams of Pantagruel”, 1565, published by Richard Breton

“The Drolatic Dreams of Pantagruel”, 1565, published by Richard Breton

The word “grotesque” first appeared in English in the 1560s, borrowed from French and ultimately derived from Italian grottesca, meaning “of a cave.” It originally described the unfamiliar ornamental paintings found in the underground ruins of Rome, then known as le Grotte (“the caves”), often depicting imaginative vegetal forms with the anthropomorphic. One of the earliest uses of the word appears in Montaigne’s Essays, when he reflects upon applying the forms and themes of the decorative arts to literary style.

Considering the proceeding of a painter’s work as I have, a desire hath possessed me to imitate him. He maketh choice of the most convenient place and middle of every wall, there to place a picture labored with all his skill and sufficiency; and all void places about it he filleth up with antique foliage or grotesque works, which are fantastical pictures having no grace but in the variety and strangeness of them. And what are these my compositions in truth, other than antique works and monstrous bodies, patched and huddled up together of divers members without any certain or well ordered figure, having neither order, dependency, or proportion, but casual and framed by chance.” — Montaigne 5

Closely tied to satire and tragicomedy, the grotesque became an artistic tool for expressing grief, absurdity, and the contradictions of existence. Defined by doubleness, hybridity, and metamorphosis, it merged the comic with the terrifying, the human with the monstrous, and the real with the surreal. Thomas Mann labeled it the “genuine antibourgeois style.”6

The essential principle of grotesque realism is degradation, that is, the lowering of all that is high, spiritual, ideal, abstract; it is a transfer to the material level, to the sphere of earth and body in their indissoluble unity.1

If Rabelais’ carnivalesque turned social relations inside out, the grotesque was the expression of its substance. Laughter was not merely conceptual but physical — embodied in distorted, porous, unruly bodies that defied containment. Unlike the rigid, idealized church and state sanctioned art, the grotesque body was always amorphous and unfinished — swallowing, excreting, swelling, bursting — a universal, joyous transformation forever negotiating the boundaries between self and world. Rabelais’ giants were the ultimate grotesque figures, consuming the world indiscriminately, reducing everything to food, drink, and waste. Their scatological acts, obscene yet fertile, rejected bodily restraint and spiritual asceticism, celebrating the raw physicality and excess of life from which the world is nourished and renewed. Death, decay, and bodily distortion were moments of transformation, breaking down the old to make way for the new. The world was ever-revolving, resisting closure or perfection. Without carnival and the grotesque, when order is preserved through sterility and fear, one is left with a world stagnant and lifeless.

The material bodily principle in grotesque realism is offered in its all-popular festive and utopian aspect. The cosmic, social, and bodily elements are given here as an indivisible whole. And this whole is gay and gracious.”1

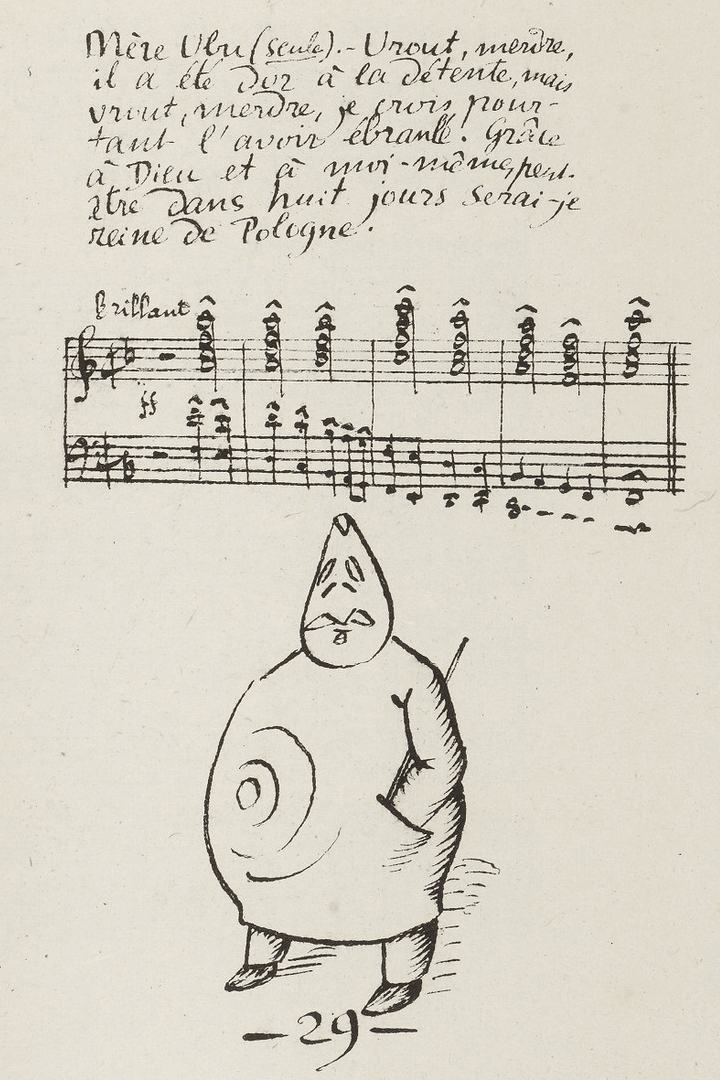

M E R D R E!

Fast forward to fin-de-siècle, Paris. Rabelais remained popular in the city’s cafes and cabarets frequented by bohemian artists. The eccentric Alfred Jarry (1873 – 1907) had spent years experimenting with puppet and theatrical adaptations of Pantagruel, employing Rabelais’ linguistic inventiveness, scatological humor, and irreverence for authority. Continuing the Rabelaisian fusion of obscenity and erudition, Jarry employed a bizarre mix of slang, puns and coded language, delivered in unusual speech patterns. His 1896 burlesque Ubu Roi famously opens with the howling of “Merdre!”, a made-up word sounding like a slurred enunciation of “merde” (shit).

A parody of Shakespeare’s major tragedies, Ubu Roi is a grotesque spectacle of power, cartoonish brutality and farcical ambition. As the play begins, the central figure, Père Ubu, is convinced by his wife to lead a revolution, overthrowing the monarchy to make himself king. Inspired by the imagined life of a despised school teacher from Jarry’s boyhood, Ubu is a giant buffoon — “fat, ugly, vulgar, gluttonous, grandiose, dishonest, stupid, jejune, voracious, greedy, cruel, cowardly and evil”.7

He is not exactly […] the bourgeois, nor the boor: he is more the perfect anarchist, except that he possesses all those eminently human qualities that prevent all of us from becoming the perfect anarchist, namely cowardice, filth, ugliness, etc. Of the three souls described by Plato: the head, the heart, and the gidouille, in him only the last is less than embryonic. — Alfred Jarry 7

The “gidouille” Jarry refers to is the spiral on Ubu’s belly, a symbol of his physical bloating, of the lower body and the power of its appetites, the origin of Ubu’s gluttony and violence. An antihero for the modern world, Ubu typifies the libidinal excess of every individual in society, not just its privileged or outcast, and so the play makes its attack from within, inviting the audience to laugh at what it fears most — what Jarry called “its own ignoble self.”8

Like Rabelais’ carnivalesque, Ubu Roi wielded laughter and the grotesque as a destabilizing force to strip away all pretense and expose authority in all its absurdity. The production’s only performance was met with scandalized and hostile reception. The play shattered theatrical convention, leaving a wreckage from which modern art movements like Dada, Surrealism, and the Theatre of the Absurd would reinvent the stage.

“Today even ridicule is sought after, it must be seized upon and it has its place in poetry because it is a part of life in the same way as heroism and all that formerly nourished a poet’s enthusiasm … [Ubu Roi] is timeless, placeless, it shamelessly displays what civilization tries hard to hide, and that is more than lavatory brushes and schoolboy swearwords, it is an aspect of truth.” [^Barbara Wright]

-

Bakhtin, Mikhail. Rabelais and His World. Indiana University Press, 2009. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6

-

Pillard, Guy-Édouard. Le Vrai Gargantua : mythologie d’un géant. Imago, 1988. ↩

-

Rabelais, Francois. Gargantua and Pantagruel. Translated by J.M. Cohen. Penguin, 1986. ↩

-

Breton, Richard. The Drolatic Dreams of Pantagruel. 1869. ↩

-

Goodwin, James. Modern American Grotesque: Literature and Photography. The Ohio State University Press, 2009. ↩

-

Clark, John R. The modern satiric grotesque and its traditions. 1991. ↩

-

Brotchie, Alastair. Alfred Jarry: A Pataphysical Life. MIT Press, 2015. ↩ ↩2

-

Jarry, Alfred. Ubu Roi. New Directions Books, 1961. ↩